ST. HELENA ISLAND — On a bluebird spring day, Walter Mack and Jimmy Wright are on Wright’s farm, talking about the things farmers talk about: the weather, when to put crops in, problems with deer and other matters of that ilk.

With a colorful career that included stints in the military, law enforcement and as a nightclub owner, Wright is in the midst of his first full season as a farmer, working 10 acres of family land on this Beaufort County sea island. At 76 years old, it’s a turn of events he never saw coming.

“I never thought I’d be a farmer. I never had any interest in it,” Wright said.

Wright’s wife, Bernice, rolled up in a utility vehicle from another corner of the farm to join the conversation, a raising cloud of dust into the breeze. She offered her thoughts on her husband’s newest endeavor.

“I did not want to hear that. I grew up on a farm, and that was hard work,” she said.

Despite the initial resistance, it’s clear that the pair are in the effort together. Bernice Wright cares for the goats, while Jimmy Wright handles the crops. He’s picking up where his father left off. His father farmed on St. Helena for several decades until his death in 1988. Memories of the discrimination his father endured as a Black farmer at the hands of federal agencies that were supposed to help him left Wright with an inherent distrust of government agencies like the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

It’s a perspective that Mack has encountered time and time again.

“At that time, these guys didn’t trust the government. The government wouldn’t help them or give them the right information.

Walter Mack

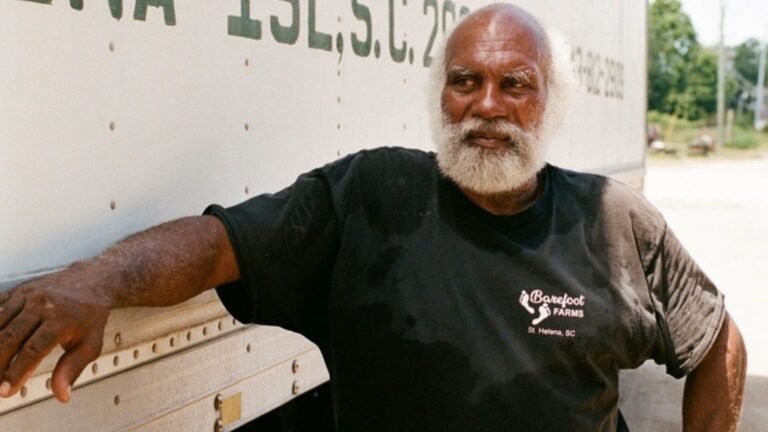

For the last year and a half, Mack’s job as a field agent for the Beaufort Conservation District has been to repair and improve the relationships between the USDA and farmers of color in the county, and ensure that farmers take advantage of every resource available to them so they can maximize the value of their agricultural land.

Funded by a grant from The Nature Conservancy in South Carolina, Mack set out to reach every small-scale farmer of color in Beaufort County and start a conversation about improving the value of their land.

“How do you create a high-value-per-acre crop on these small lands? You’re not going to make any money farming 10 acres of corn. You have to create a high-value product and that requires markets and a different approach,” said David Bishop, coastal and midlands conservation director for The Nature Conservancy.

Conservancy in South Carolina

The Nature Conservancy is well known for its national and international conservation efforts. In the southern reaches of the Lowcountry, the group has played a major role in large conservation projects like Slater-Buckfield and Gregorie Neck as well as the recent acquisition of the 2,700-acre Chelsea property.

While large-scale land preservation is, without a doubt, the organization’s focus, The Nature Conservancy in South Carolina was also looking at novel solutions for protecting smaller parcels that contribute in aggregate to the broader landscape. That focus has resulted in efforts to help small-scale farmers maximize the value of land used for agriculture. The logic is simple: Profitable farms are more likely to remain farms and less likely to be sold for development.

“There’s still the original goal of preserving the landscape but with a twist of using market forces and removing barriers that put people in a position to make more money,” Bishop explained. “My interest in this is keeping small farms and forests intact. You can’t buy it all.”

Moving from a concept to practice was facilitated by a $60,000 grant in 2023 from the conservancy to the Beaufort Conservation District to help address the challenges facing farmers in the county.

“This was a gift from heaven,” said Leslie Meola, district manager for the Beaufort Conservation District.

A lifelong resident of St. Helena and a farmer himself, Mack was the ideal candidate for the job. He had the local connections, the farming expertise and a familiarity with the bureaucracy. Most importantly, he was trusted by the community.

“Historically, small farmers do not trust the government. There’s some history behind that,” Mack said. “They don’t feel like they’ve been treated fairly. I serve as the conduit to the USDA office.”

Low Hanging Fruit

Starting in mid-2023, Mack began visiting every farm in the area. His job was, he said, to find the barriers that kept farmers from maximizing their profits. Some of the issues were simple. There were farmers who didn’t have a farm number assigned. Without that number, it’s impossible to participate in any USDA programs. So, Mack helped those farmers get their numbers.

He also found that some farmers were paying too much in property tax.

“A lot of farmers didn’t know that agricultural land is taxed at a lower rate than regular homeowners. They were paying thousands of dollars in taxes that they didn’t have to pay,” Mack said.

Meola expanded on the issue, noting that Mack wouldn’t just tell the farmers about the tax breaks they might qualify for. He’d go to the tax office with the farmers and help them file the necessary paperwork. If an application got kicked back for some reason, Mack helped resolve the problem. In the past, farmers, he said, would often quit once they hit a roadblock like that.

“They’d give up. ‘They don’t want to do anything to help me.’ That’s what I always hear,” Mack said.

Further complicating the matter is that federal bureaucracy better equipped to handle large, corporate farms than small, independent farmers.

“The terminology they use for these large farms with a department of lawyers is the same that they use for small farmers. That don’t work,” Mack said.

To help maneuver around the reluctance of farmers to deal with federal agencies, Mack often had USDA representatives set up shop in the Beaufort Conservation District office on Lady’s Island. It was neutral turf, and local farmers felt more comfortable there.

The grant from The Nature Conservancy funded Mack’s work for the first year. Still an employee of the conservation district, the cost of his ongoing work is shared by the district and the Natural Resource Conservation Service, which exists as part of USDA. With the shift in funding, the scope of Mack’s role has expanded.

“His mission now is now not just focusing on farmers of color. It’s farming in general, any farmers,” Meola said.

Mack identified 29 small farm in the county in his first year, though a few didn’t meet USDA’s definition of a farm as an agricultural operation that generates at least $1,000 a year. Most of the county’s farms are on St. Helena Island, and there are a few north of Beaufort in the Seabrook area. Most of the farms are less the 50 acres in size.

“The closer you get to Hilton Head and Bluffton, no farmers. I think we found two farmers over there,” Mack said.

Real-World Challenges

Earl Brown, 72, was born and raised on St. Helena, but left in 1968. He settled in Boston and worked as a transit driver until his retirement in 2007. After retiring, he returned to the island of his childhood and took up farming. Working six acres, he’s growing corn, squash, watermelon, okra and cantaloupe.

“People like a variety,” he said.

Farming on rented land, he does much of the work by hand and makes minimal use of chemicals.

“He uses blue steel. Do you know what that is? It’s a hoe,” Mack said, laughing at his own joke.

Relatively new to farming, Brown said he didn’t have reason to distrust the federal government, but he expressed frustration that he couldn’t get help with the one item he needed most — fencing. Conflicts between farmers and deer on St. Helena are frequent and costly. Brown installed deer fencing this at an out-of-pocket cost of about $7,000.

“Last year, the deer ate my okra, watermelon, potato, peas,” Brown said. “If I could have gotten some help with that, it would have been appreciated. But you do what you need to do. You don’t put the fence up, you’re not going to get no crop.”

Mack noted that he looked for help for Brown’s deer fence, but the USDA had no funding available. He found assistance for cattle and hog fences, but nothing for omnipresent deer. It’s possible that funding will become available later in the year, Mack said, though by that time it’ll be too late to be of any use to Brown.

At his farm down the road, Wright spent the better part of two years clearing the 10 acres he now farms, doing all the work himself. Last season he planted seven rows of collard greens as a proof of concept, and he produced a successful crop that was shared with family, neighbors and the goats.

“They got their share. They loved it.” Wright said of the goats.

Given his father’s history, Wright needed some convincing before signing on with the USDA. Mack talked him into meeting with the federal representatives at the Lady’s Island office, and it was a productive meeting, at least to a degree. Wright scored help with funding for a pair of greenhouses and a deep well used to provide water for the goats on the farm. But like Brown, he was frustrated at the lack of assistance with deer fencing.

“I needed help with fencing. This is the biggest problem that farmers have around here. Everybody says they want to help the Black farmers, but you’re not helping them if you don’t give them fencing,” Wright said

Illustrating the necessity for the work Mack does, Wright said he became aware of a grant that was available to farmers only after the application period had expired. Had he known about it earlier, he would have applied.

“They just don’t know what’s out there that’s available to them,” Mack said.

Looking forward, Bishop, Meola and Mack all believe there’s an opportunity to expand the work Mack is doing into neighboring counties, and Jasper County is first on the list.

“It’s about conservation, yes. It’s about preserving the ability of lands to adapt and shift. But it’s also about that sense of place, that feel of rural agriculture that’s been lost in places Bluffton and Hilton Head, but still persists in little pockets like St. Helena,” Bishop said.